One of the magic properties of HTTP, the protocol that underlies most of the communications over the web, is that it is stateless. At the protocol level, the contents of one request will not affect the handling of the next request. This, along with a clever set of layered headers, enables the web to cache most of its traffic. |

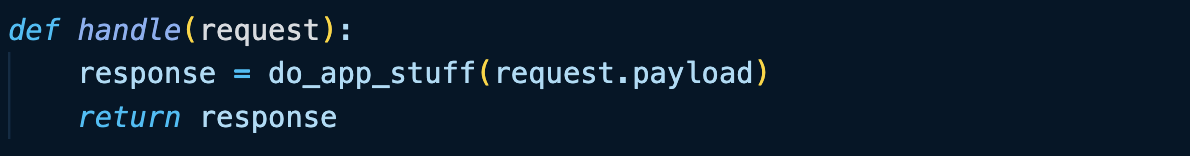

This has a cool knock-on effect. Each request can be handled by a function which receives that request as a parameter and returns a response. |

|

A number of web frameworks, such as Ruby's Sinatra, work just like that. |

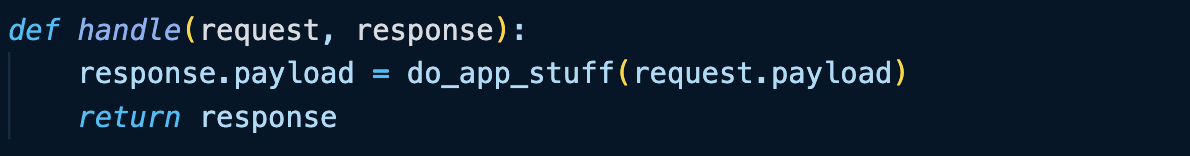

Sometimes, a response has to contain stuff related to the incoming request, so it's more convenient to pas a partially filled response passed in to the handler. |

|

JavaScript's Express works like this. |

| | | | Maybe your friends and colleagues would be interested in this kind of content. Send them to pragprog.com/newsletter and they can sign up for free. | | | | |

|

Let's Make It Complicated |

Most projects need more features that these simple request handlers provide, and frameworks such as Laravel and Rails oblige. In these, we group requests handlers into namespaces, where each namespace typically handles a single resource. That's very reasonable. |

But then, they make each of these namespaces a class definition. Each request hander is an instance method of that class. And that makes no sense. |

It's not the extra overhead of creating a controller object for each request: that's insignificant. No, the problem is that by embedding the request handling functions in a class, all of the supporting functionality is also rolled into that class. |

|

| |

Classes make it too tempting to bundle functionality. If we look at Rails, the ActionController class includes over 35 additional modules; out of the box, it provides over 370 methods to the actions you write. |

This is not the fault of classes: it's a natural human weakness. But it takes something that should be simple—a function that receives a request and returns a response—and wraps it in a complex environment. |

Don't get me wrong: the handling of a request can be complex: authentication, CSRF, websocket support, multiple response formats, and a bunch of other things. But the idea of an all-encompassing controller class that provides it all means that every request handler runs with that complexity. If you want to call one of your request handlers in isolation, perhaps to run a simple test or to setup some context for a response in a different controller, what would you need to do? You can easily instantiate a controller object, which lets you call the handler method. But what about all the rest of the context you'd have to set up? How much is needed to make your handler work. How much of that is not actually used by your handler? |

It's Not About Rails or Laravel |

You might think I'm dissing Rails or Laravel for their design decisions. I'm not. They made deliberate choices to make everything available, all the time; they felt it led to a better developer experience. |

No, my problem is that that frameworks such as these are often used as examples of how things should be done universally. Developers get into the habit of taking code that is a function with no need for state and automatically write it as a method in a class, often creating the class simply to give that function a home. Then, as the code grows, additional methods are added, until you end up with a "convenience" class full of random, but still coupled, stuff. |

And that coupling is what leads to problems down the road. It's baggage that loads down every method you write. If instead you'd just used functions, each would be free-standing, isolated, and a lot easier to work with. |

Even the best designed and written class adds coupling to your code. Next week I want to look at that coupling in more detail. |