Network Programming in Elixir and Erlang IPs and PortsTCP is also known as TCP/IP. IP stands for Internet Protocol. It’s the most common network protocol (layer 3 of the OSI model; see Appendix 1, The OSI Model). Its job is to route packets from sources to destinations. The way it does that is by annotating packets with two pieces of information: an address and a port. Addresses, also known as IP addresses, identify hosts on the network. They look like four-element a.b.c.d strings, where each letter represents an integer from 0 to 255—for example, 140.82.121.3. In network-speak, ports are a way to route packets to different programs within the same host. They range from 1 to 65535 (the possible values of 16 bits). For example, it’s standard to use port 443 to listen for HTTPS traffic and port 22 for SSH traffic. These ports have nothing to do with the Erlang data type—they just (sadly) share the same name. You’ll sometimes see address-port combinations represented with a colon separating them, as in 140.82.121.3:443. Now, enough talk—let’s see some code. Writing a TCP Client with the gen_tcp Module… In this chapter (and most of this book), we’ll use modules that are part of Erlang’s standard distribution. When it comes to TCP, Erlang ships with the gen_tcp module.gen_tcp provides a complete API for working with TCP, from creating client and server sockets to sending data and receiving data. To open a new connection, the function you want is :gen_tcp.connect/4. Open an Elixir interactive shell by typing iex in your terminal, and then type the following: | | iex> {:ok, socket} = | | | ...> :gen_tcp.connect(~c"tcpbin.com", 4242, [:binary], 5000) | | | {:ok, #Port<0.6>} |

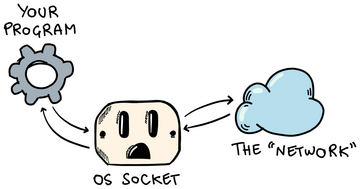

The first argument is an Erlang string with the address to connect to. It could also be a raw IP address, but we’ll get to that a bit later. The second argument is the port that the server is listening on. We’re using 4242 here because that’s what tcpbin.com uses. The third argument is a list of options, and the fourth argument is a connection timeout in milliseconds. Milliseconds are the “lingua franca” for timeouts on the BEAM—see things such as timeout:minutes/1 or Kernel.to_timeout/1. The :binary option is important: if we don’t pass it, all data sent and received through the socket will be in the form of charlists rather than binaries. We generally don’t want that, since binaries are more efficient and usually easier to work with. … The return value is an {:ok, socket} tuple. socket is a data structure that wraps the OS-level socket we talked about earlier. This returned socket identifies our client connection, and we can use it to exchange data with the server. Elixir prints the socket as #Port<...> because a socket is an Erlang port. We’ll talk more about ports later in the book. The other possible return value of :gen_tcp.connect/4 is {:error, reason} in the case that something goes wrong. Returning {:ok, value} or {:error, reason} is a common pattern in Elixir and Erlang when dealing with functions that can fail. In the case of :gen_tcp.connect/4 and most other :gen_tcp functions, reason is a representation of a POSIX error code, such as ECONNREFUSED (represented as :econnrefused). The Erlang documentation has a whole section on POSIX error codes that you can use for reference. Well, time to send some data. To do that, we can use .send/2: | | iex> :gen_tcp.send(socket, "Hello, world!\n") | | | :ok |

|